Dr. Alice C. Linsley

The Hebrew inheritance laws are complex because high-ranking

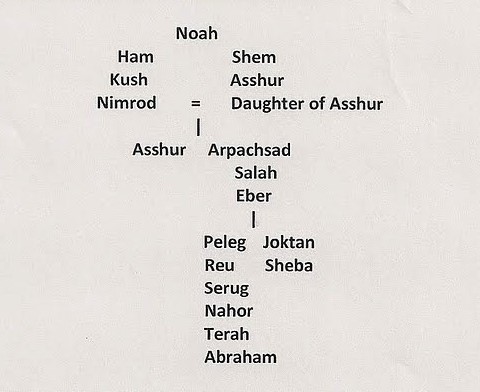

rulers such as Abraham had two first-born sons. Abraham's first-borns sons were Joktan (born of Keturah, Gen. 25) and Ishmael, but neither of these sons were Abraham's proper heir.

Among the early Hebrew the proper heir was the first-born son of the first wife, usually a half-sister, as was Sarah to Abraham (Gen. 20:12). This explains the deep sorrow of Abraham and Sarah that she was unable to bear children. It also sheds light on the story of Hagar and Ishmael’s banishment. Having provided a proper heir for Abraham after years of barrenness, Sarah became angry when she thought that Abraham’s love for both Ishmael and Isaac might lead him to divide his territory between them, as Eber did for his sons Peleg and Joktan.

Genesis 10:25 reports: “To Eber were born two sons: the first was called Peleg, because it was in his time that the earth [eretz] was divided, and his brother was called Joktan.”

The word eretz has multiple meanings: earth, land, soil, and territory. Since this passage deals with royal sons, the most appropriate word choice in this context is “territory”. It the appears that Eber divided his territory into two, assigning separate regions to each royal son. Peleg ruled over one territory and Joktan over the other. Abraham was a descendant of Peleg, and his half-brother Haran likely was a descendant of Joktan.

The clan of Jacob (Israel) went into Egypt, but they were not the only Hebrew clan. Clearly, some Hebrew were never in Egypt. The story of the Exodus does not apply to them. It is also likely that some Hebrew people remained in Egypt as they had deep roots in the Nile Valley.

In the Hebrew social structure, provision was made for the sons of high-ranking rulers to receive an inheritance, and grants were made to the sons of concubines. The value of the grants likely depended on the dowery of high-status concubines and on the generosity of the patriarch. Grants included land, servants, herds, camels, linen, leather goods, and articles of gold, copper, silver, and bronze.

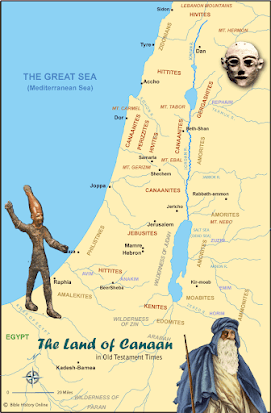

However, only one son could assume control over the territory of his father and that was the first-born son of the principal wife. In Abraham's case, that was Isaac. He received the bulk of Abraham's wealth and assumed control over Abraham's territory which extended between Hebron and Beersheba. Abraham’s other sons received gifts and were sent away from Isaac (Gen. 25:6). The gifts helped the sent-away sons to become established in their own territories. This practice preserved Abraham’s territory intact and led to the wide dispersion of the Hebrew ruler-priests even before Abraham's time.

The Hebrew practice of endogamy played a role in amassing and preserving wealth. Their distinctive marriage and ascendancy pattern allowed for a smooth transition of power among the ruler-priests. It also made it possible to keep territories intact and to preserve wealth. Wealth among the early Hebrew involved herds, servants, gold, copper, and water resources. Some Hebrew controlled commerce on the rivers and major water systems. This provided income from cargo taxes. A major trade route between Egypt and Mesopotamia ran through part of Abraham’s territory and this likely provided him with a source of income. He also held the water rights to wells he dug in Gerar (Gen. 26:15).

It is evident from the biblical data that Abraham's clan observed an ancient code or tradition that pertained to rights of inheritance. His authority was attached to the ruler-priest caste into which he was born and was reinforced by his observation of this code. The early Hebrew believed that the tradition received from their ancestors was not to be changed. They preserved their religion heritage, ethnic identity, and wealth by marrying exclusively within their caste (endogamy).

No comments:

Post a Comment